This is a transcript of a talk I gave as part of the book launch for A *New* Program For Graphic Design by David Reinfurt at the Lewis Center for the Arts, Princeton University.

My name is Jonathan Zong. I currently work at MIT where I think about the social, ethical, and political commitments that are brought to bear in the design of technology. Before I get to that, I think it’s worth pointing out that the conceit of this talk is a little bit artificial. Many of us don’t actually work nine to five days. What does a typical nine to five day mean in a room full of art students in a department that is sustained by the labor of lecturers and adjunct faculty? So, as for the subject of my talk, there exists some hypothetical day that according to the rules of this event would allow me to talk about the projects that I want to share with you, so I am talking about that day. I work in a computer science department in a subfield of computer science called human-computer interaction. And this is kind of a way for me to continue to engage with the discourse of design while also existing in spaces that are very close to the production of technology itself.

And why is it important to think about its social, political, ethical commitments? Well you might have heard of something called deepfakes, which are a type of AI-generated video which anonymous internet men have used to swap the faces of celebrity women onto the bodies of porn performers. This is clearly wrong because it’s non-consensual. But in a talk I gave in April at a conference called Theorizing the Web, I argue that all of this type of technology, AI technology, is founded on non-consent. The amount of massive large-scale data collection that is required to create these technologies relies on a surveillance apparatus that is kind of embedded in the way that the internet is structured and economically run. So there’s a set of concerns I hope to articulate around images and representation as instruments of control, and the representation of bodies in numbers, and the role that consent does and doesn’t play, that I hope will come through in this talk.

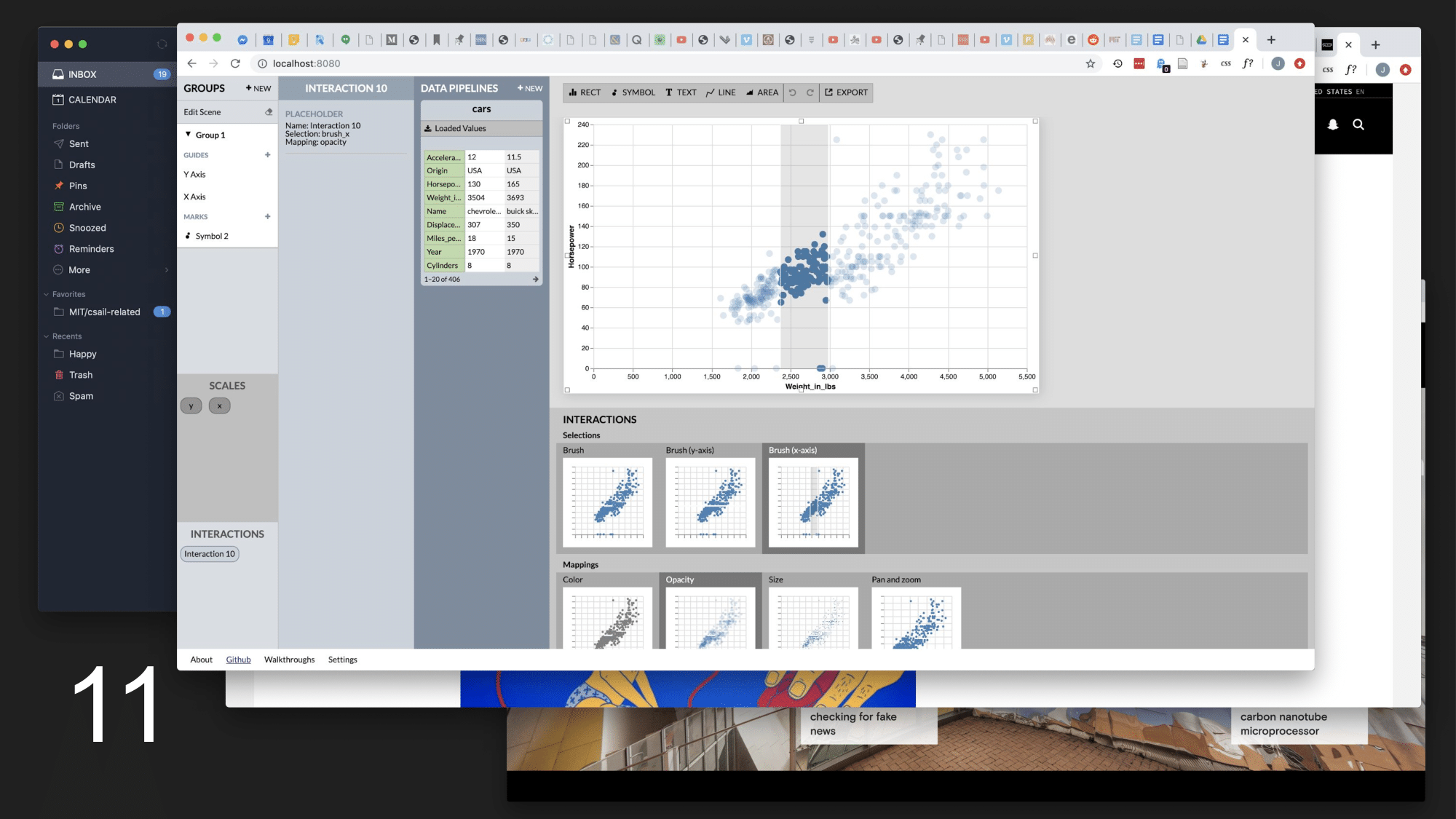

So consent itself assumes informedness. The idea is that you have to be aware of the decision that you are making, the risks and benefits of your possible participation in data collection. The research group that I work with studies data visualization, and much of my work with this group has involved software interfaces that are designed to help people be able to create data visualizations without having to code. This would be great for people who need to communicate complex quantitative ideas to other people. And so this project is called Lyra, it’s kind of like an Adobe Illustrator-like thing for data where you can create shapes and then bind data fields to those shapes to generate visualizations. It’s well understood how to make static images in this way; my contribution here is an interaction model that allows you to directly demonstrate interactive behavior onto those visualizations, which is very complex to code.

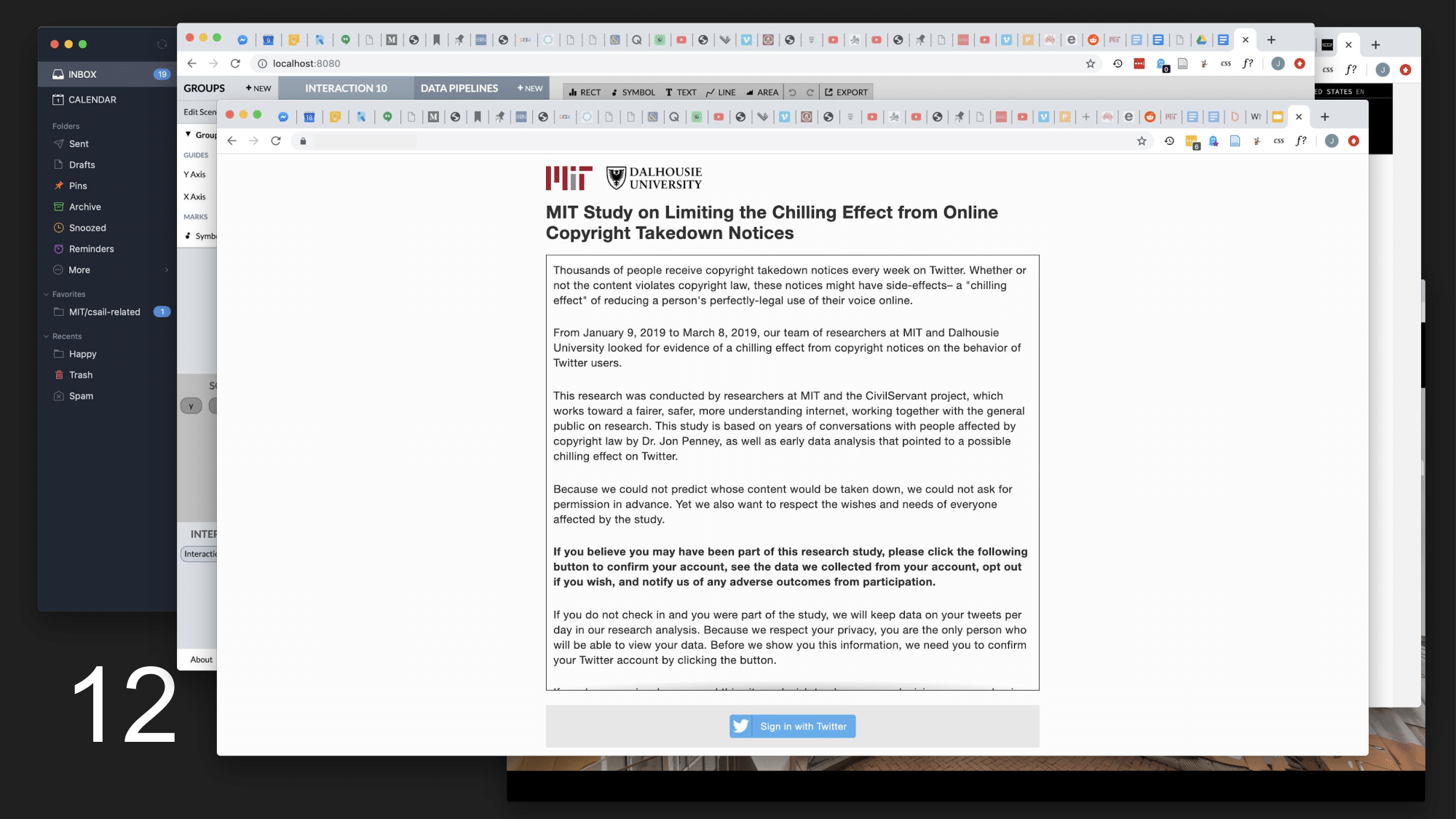

My work explores consent through other methods as well. With my collaborators who were at Princeton and are now at Cornell, I worked on a system that helps researchers who do large-scale behavioral research on the internet manage the ethics of that research. So if you want to learn something about how people act online, and you need to observe a lot of people. This is great for social scientists, because there’s a lot of people online, but you don’t always know ahead of time who’s going to be online on a given day. Or even if you could, how do you ask everyone for consent without kind of giving away the goose (in terms of the validity of your study)? So there’s a method called debriefing which we borrow from fields like psychology where you retroactively get consent. And my software interface allows researchers to message all their study participants and explain the purpose of their research and ask them whether or not they want to opt out of data collection.

In the course of doing this work I also started to try to critically appraise the concept of consent itself and its misapplicability to the context of data protection in general. Many regulations such as the EU’s GDPR and the California Consumer Privacy Act codify informed consent as the only way to gauge the legitimacy of data collection. But there’s fundamental mismatches between the individualist model of the rational decision-making data subject and the collective nature of data. A single data point is not useful unless it’s linked in the aggregate. The disparate outcomes of AI-based surveillance fall differently on different communities. So we need a way to imagine what it’s like to collectively accept or refuse these technologies.

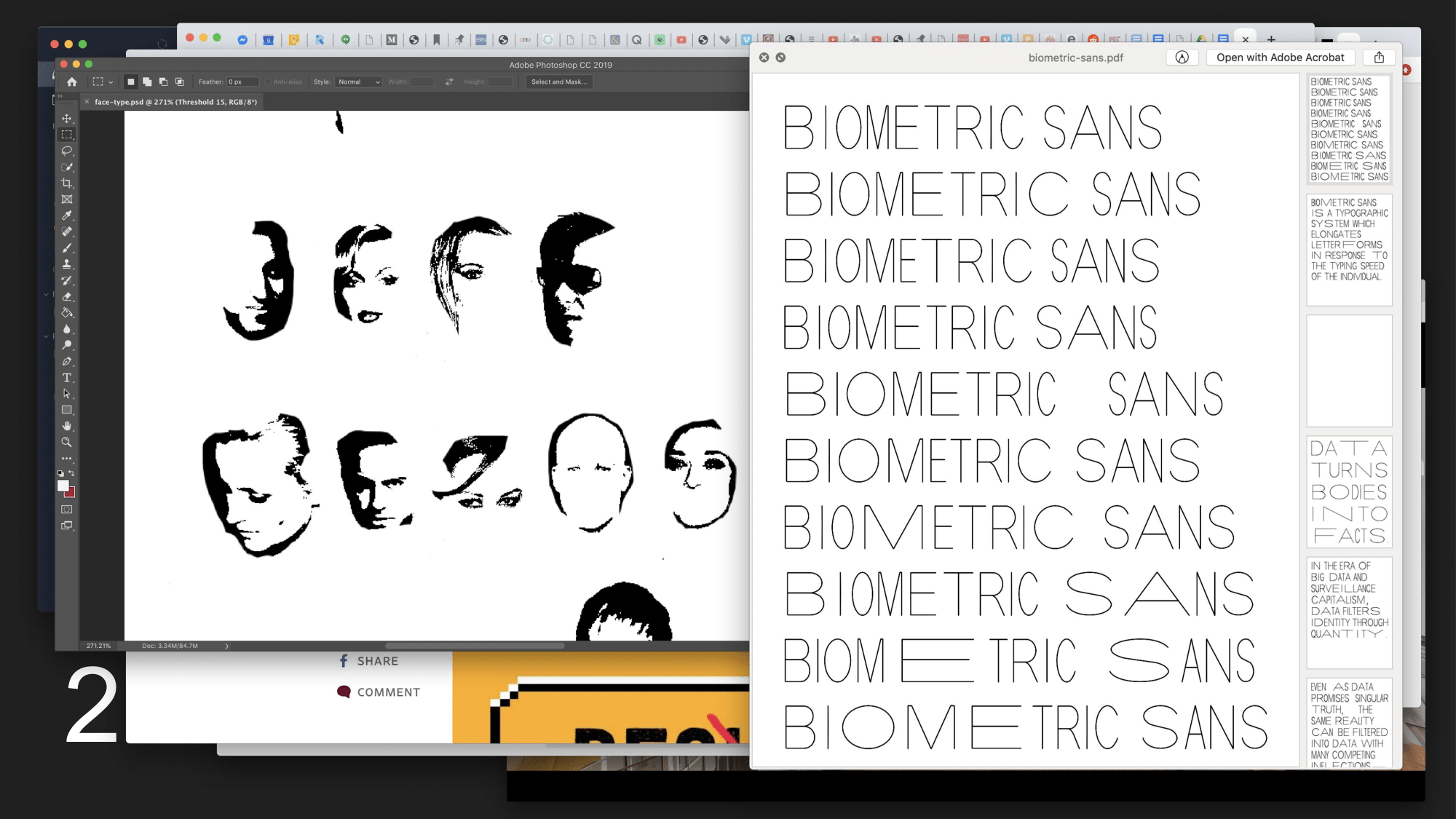

I’m also trying to make art about it. Biometric Sans is a typographic system that I made my senior year as David’s student that stretches and shrinks letters based on the typing speed of the individual. It was a way for me to reinsert embodiment into the act of digital writing. But what does it mean that embodiment in this case is purely understood through surveillance and measurement? So my current project, the Jeff Bezos text on the left, is a typeface that I’ve made by taking faces from a facial recognition dataset and erasing bits of them until they make letters. And I’m trying to think about this condition of surveillance, which is really hyper-visibility, through this intervention of erasure. And I’m kind of interested in the way that you have to not read these faces as faces in order to read them as letters. There’s kind of a forced choice here between the part and the whole.

I also try to complete the triangle between research and design practice by teaching. In the spring, along with my sister who is an English literature researcher, I’m co-teaching a course at Tufts University called AI, Justice, Imagination: Technology and Speculative Fiction. Our syllabus will pair science fiction and speculative fiction texts with critical data studies research, criticism, and interdisciplinary analysis in an effort to formulate a language around which to think about imagination, as Ruha Benjamin says, as a site of contestation. Why are people often forced to live in other peoples’ speculative imaginations? And, it’s also a great excuse for me to hang out with my sister! So that’s really fun. And read a lot of books.

So I guess, for the students in the room, I kind of want to encourage you think about the questions you’re interested in: why are you interested in them, and what is the best way for you to ask them in a way that no one else is? For me, all these questions in technology, I feel particularly positioned to interrogate through the lens of design, and of interface, because that is my experience and my subjectivity, and I feel like that’s the thing I can offer to the spaces that I am in. And so my choice to go to MIT really is a decision about who my peers will be, and how my work can have influence in the communities that I engage with, whether that’s communities of theory or of practice. David calls graphic design “the most liberal of arts”—I think that’s super appropriate. You really can just use it as a methodology or frame through which to think about whatever you want, and whatever feels like it expresses your values.