The following is a transcript of a talk I presented at Theorizing the Web 2019 as part of the panel Internet Connection.

■

Hi, my name is Jonathan. I study human-computer interaction at MIT’s computer science and artificial intelligence lab. I will be speaking about issues of consent and autonomy in deepfakes, a class of technology that has been used to create convincing fake videos of people.

This talk includes discussion of non-consensual image-sharing and will briefly reference depictions of sexual assault. To be clear, I am not showing explicit imagery in this presentation. But this can be a difficult topic, and you are invited to opt-out of this talk if it brings you discomfort.

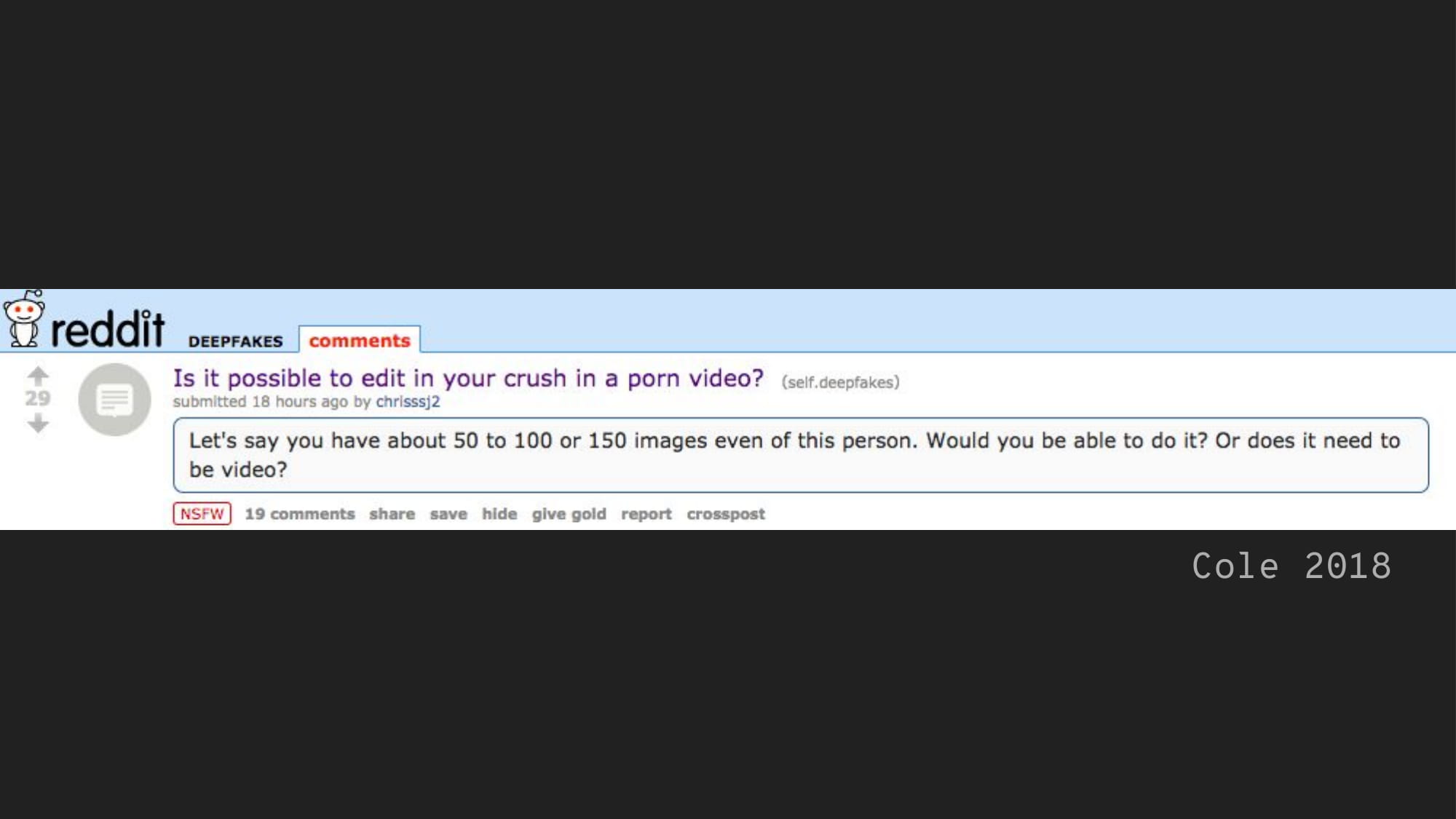

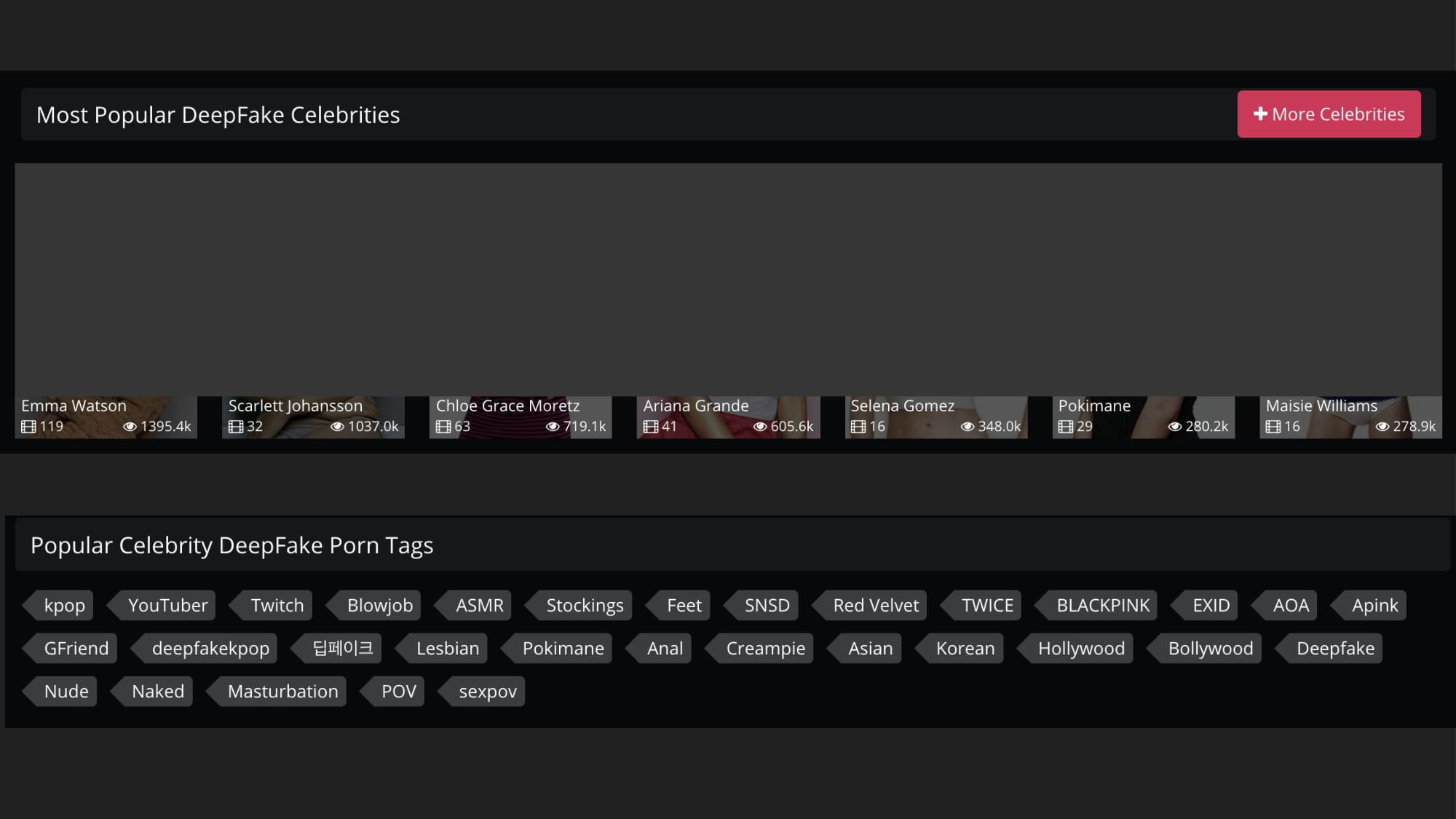

So, maybe you’ve seen this in the news: Reddit user “deepfakes” made an uproar by swapping celebrity faces onto porn bodies in late 2017. The story was first brought to public attention by Vice’s Samantha Cole, whom we’ll hear from later in a keynote session. An anonymous internet man, using knowledge from publicly available research and open source software, turned non-consensual pornography of celebrities into a cottage industry.

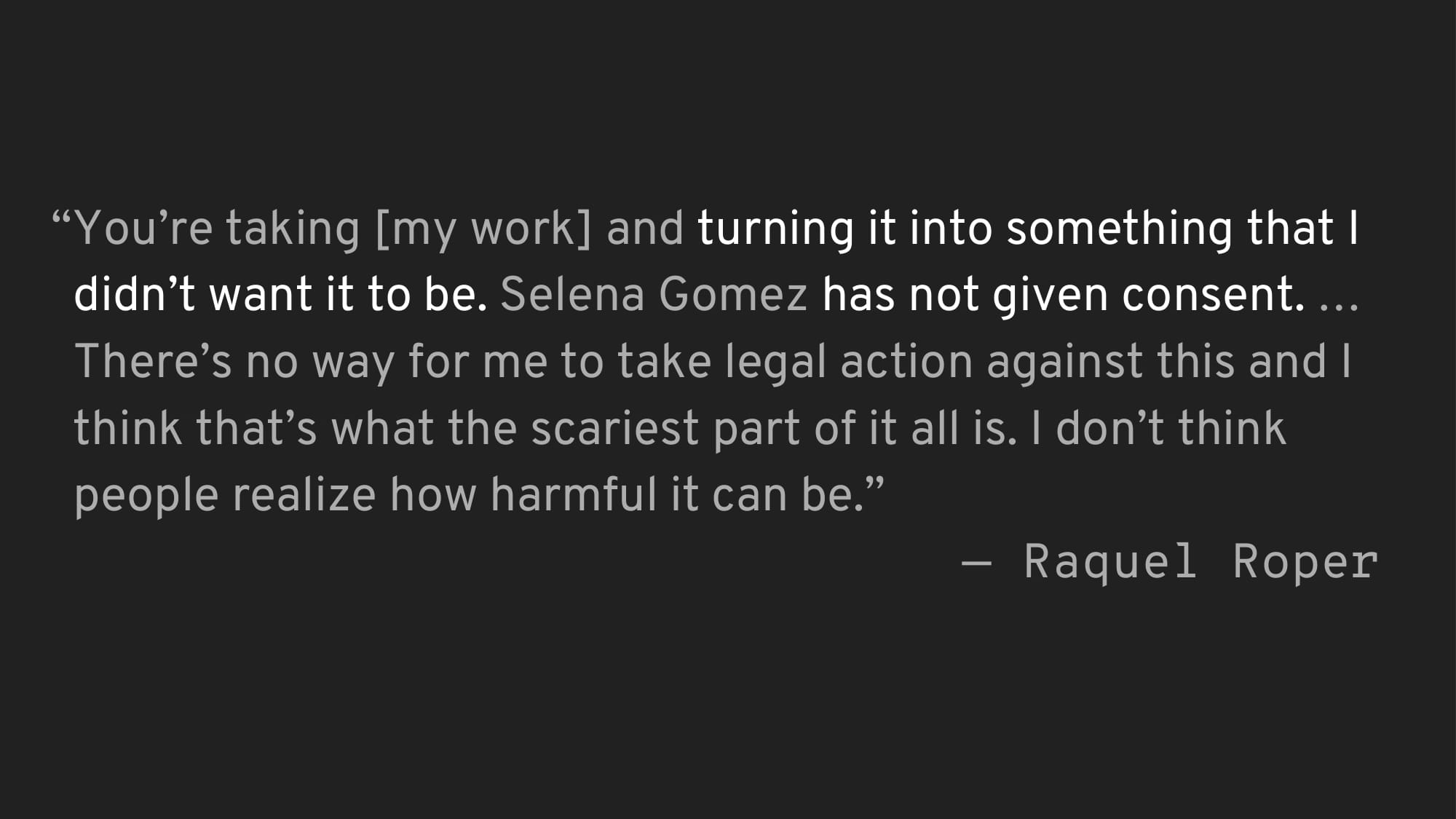

Deepfake celebrity porn violates the consent of not only the celebrities whose faces are swapped into porn videos, but also the performers whose bodies act as surface. Adult performer Raquel Roper’s video was used in a face-swap of Selena Gomez; she says that her work was “turn[ed] into something that [she] didn’t want it to be,” without either woman’s consent or any legal recourse.

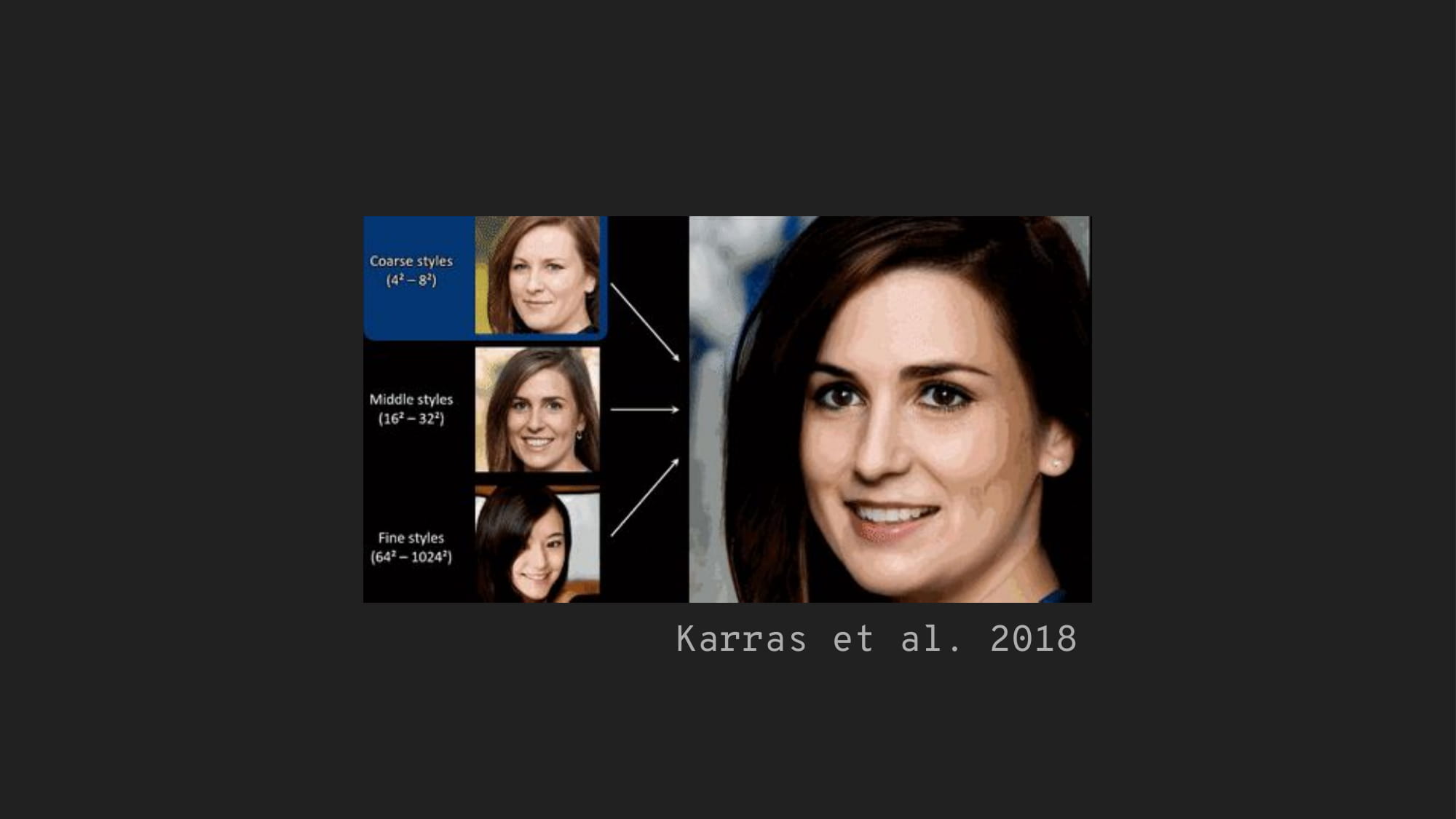

But since 2017, AI techniques have come far. There now exist the building blocks to make convincing fake video not only controlling faces and expressions,

but also poses and movements. Furthermore,

neural networks can synthesize realistic images of non-existent people.

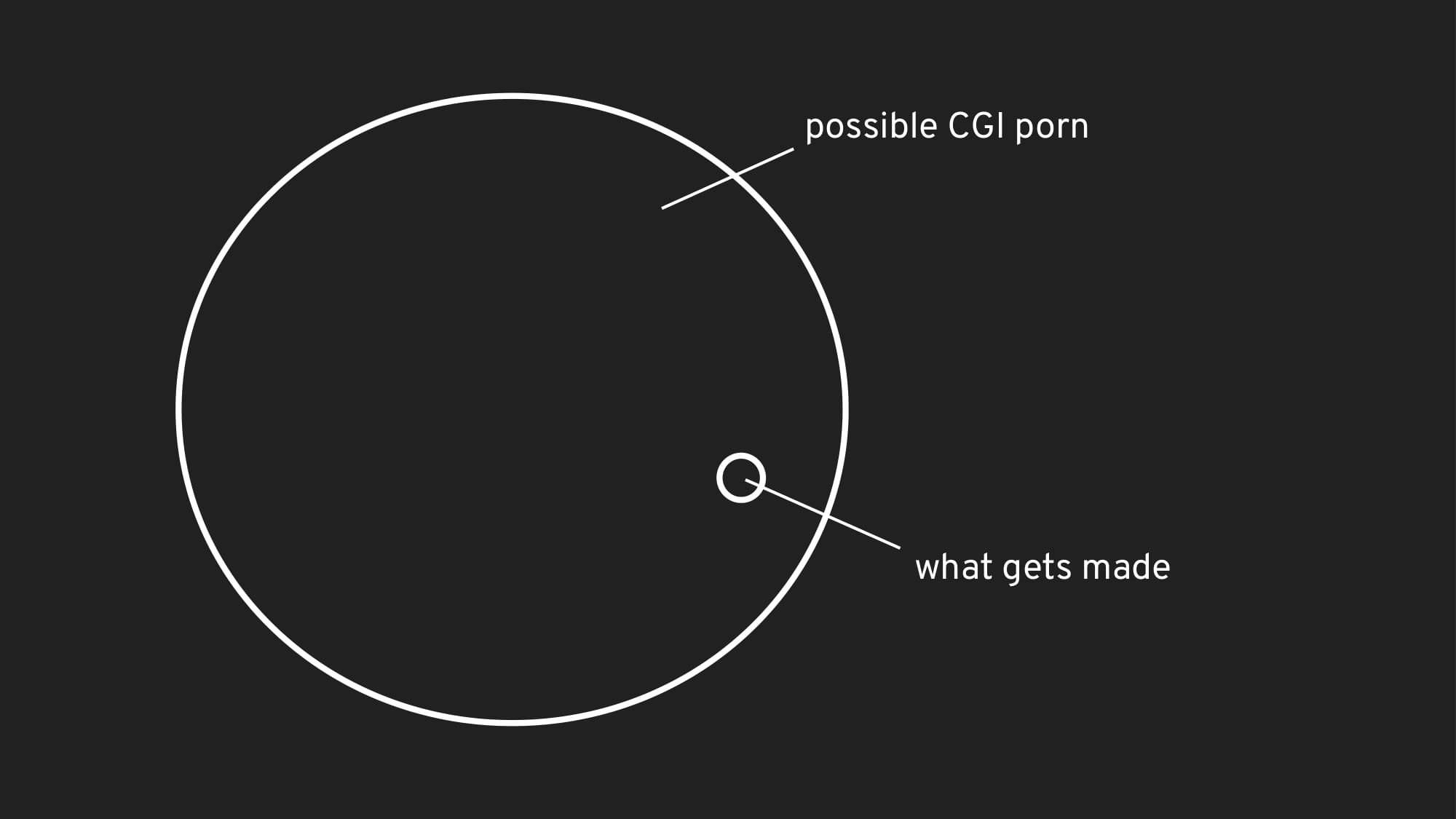

Deepfake celebrity porn is wrong because it is non-consensual, violating the subject’s autonomy. But what about fully synthetic porn from an artificial likeness that doesn’t correspond to a real person?

In this talk, I want to take a walk down the speculative (and arguably probable) future in which photorealistic synthetic porn is commonplace. I want to highlight some ways that such developments might show us how deepfakes complicate consent.

I’ll try to organize these thoughts in three sections around these questions: Who can or does consent? What are they consenting to? And how might we confront the limitations of consent?

And to facilitate this conversation, I’ll propose a working definition of consent here that we might, for now, agree on.

Autonomy is the idea that people have free will and the capacity to freely make choices.

Consent, then, is a voluntary, informed choice to enter into a power relation, based on the expectation that autonomy will be mutually respected.

Let’s start with this question of: who does or can consent?

Do fake people consent? The point of consent is so that nothing happens to anybody against their will. Imaginary people dreamt up by AI don’t have wills, so it seems like there’s no problem here. Some have suggested that synthetic porn that doesn’t involve performers could have benefits, like reducing the risk of exploitative sex work, or allowing new creators to represent diverse bodies and viewpoints.

Well, we do already have synthetic porn, although it’s not photorealistic yet. Consider machinima porn, which uses computer graphics to create sexualized depictions of video game characters. In 2014, two anonymous internet men who call themselves StudioFOW created a viral video of Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider series—essentially a virtual celebrity. The video was a violent depiction of in-game villains raping her.

In real porn, depictions of non-consent are performed by consenting actors. Synthetic porn enables depictions of scenarios that real people can’t physically create or wouldn’t consent to. But despite the expanded possibility, in practice machinima porn often retreads predictable scenarios of control and submission along gendered power dynamics.

The question I want to raise here is that consensual vs non-consensual doesn’t always completely capture the notion of just vs unjust in a broader sense. If consent is the only standard for whether something is harmful, StudioFOW gets to reify patterns of violence against non-men and brush it off as a victimless crime.

It’s often taken as given that AI is becoming increasingly democratized. Just like machinima, deepfakes may soon be held up an example of a thriving amateur creative scene with tools that are accessible to everyone equally. Optimistically, the hope might be that equal creative access levels the playing field for bodies that have been until now only been rendered through the male gaze. We might imagine porn that instead depicts bodies through female, queer, or oppositional gazes. But that hasn’t happened in machinima porn, and won’t happen in deepfake porn unless something changes.

While the structures of exclusion and oppression continue to exist which prevent women from participating equitably in all areas of computing work like AI research and software engineering, I won’t expect the conditions of production in deepfakes to magically change. Instead, deepfakes will allow people in power—in this case, anonymous internet men—to leverage technology to hold onto that power.

That brings me, in a way, to the next question: what do people consent to when they consent? To unpack that a bit, I’ll draw an analogy from the history of gendered oppression in computing that prefigures how the way AI operationalizes bodies today makes truly informed consent impossible.

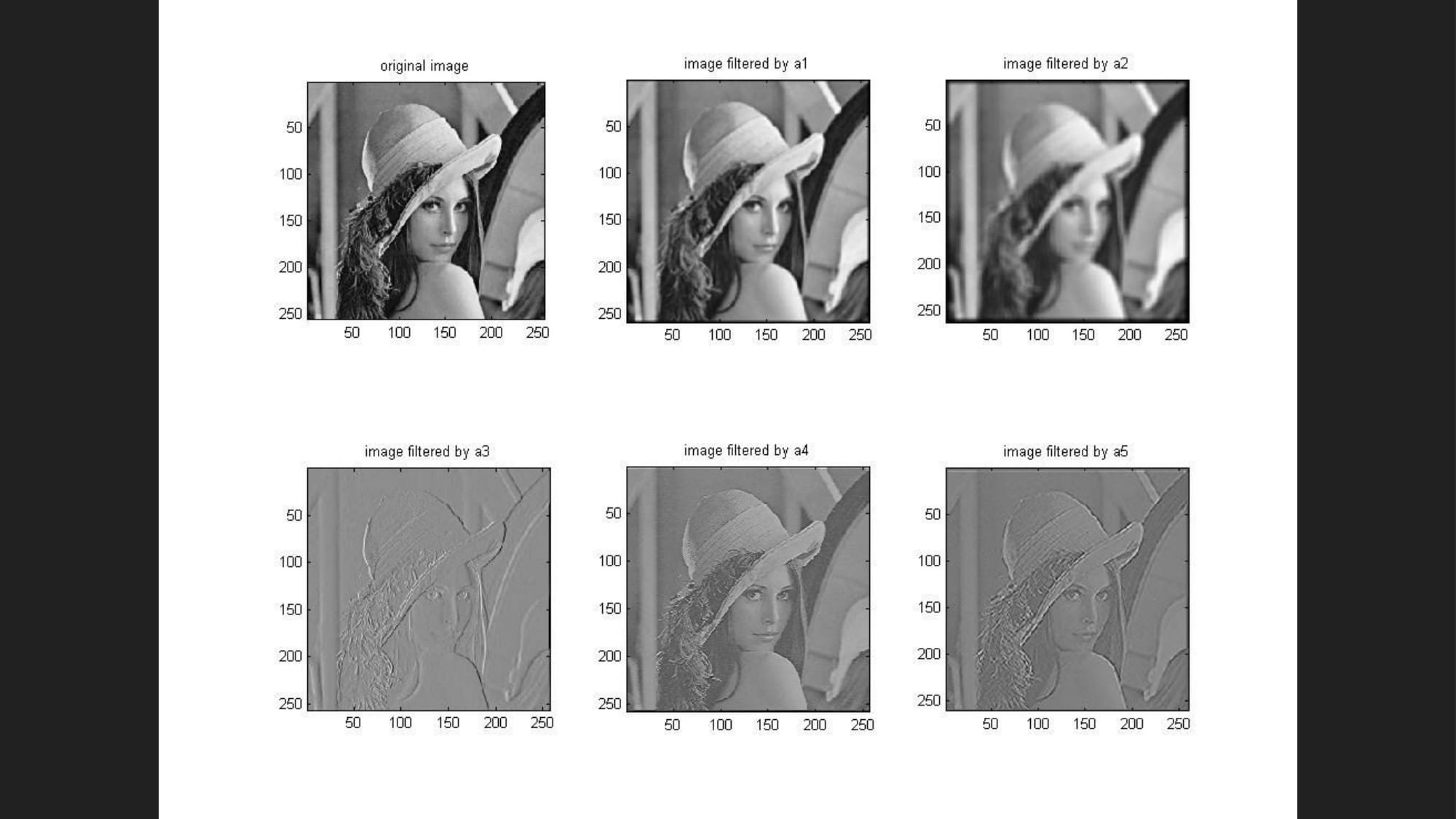

Perhaps part of why non-male gazes haven’t permeated current synthetic porn is the fact that the male gaze is built into the history of computing. For instance, in 1972 a cropped nude of Lena Forsen, who was Playboy’s Miss November at the time, became the standard test image in the field of image processing.

When she was later invited to a conference of the Society for Imaging Science and Technology to be recognized for her role in the development of the JPEG compression format, scientists in attendance were surprised she was a real person. “After some of them had spent 25 years looking at her picture, she just became this test image,” writes Wired’s Linda Kinstler.

Lena Forsen consented to having her photo published. But there’s no way she could have consented to how the photo was appropriated to test software, because there was no way of knowing that would happen when she posed for the photo. Let’s imagine that Lena consents to publish her image, then doesn’t like how it’s being used at some point in the next 47 years; how does she un-publish her image?

The use of Lena’s image has been referred to as “tech’s original sin” in the context of industry gender dynamics; but it prefigures a massive crisis of consent in technology as well. Today, the normal, mundane practices of AI researchers involve using peoples’ images without their knowledge or consent.

IBM has a massive dataset of face images harvested from Flickr that tests the surveillance tech it sells to NYPD.

Facebook trains face recognition models on tagged user-uploaded photos because they come with identity labels for free.

And perhaps most horrifyingly, the US government uses images of children who have been exploited for child pornography, US visa applicants, travelers boarding aircraft, and people who were arrested and are now deceased to test vendors’ facial recognition systems.

The possibility of synthetic porn should force us to rethink our reliance on consent as a moral barometer. Saying that AI synthesizes images of imaginary people out of nothing actually obscures the fact that these AI were trained on thousands of images of real people who didn’t consent to the AI’s eventual use. Porn of “people who don’t exist” will likely actually be porn made by collecting images of unwitting people on the internet.

Like Lena Forsen, these people may have consented to sharing these photos publicly; however, that consent is bounded by expectations of what the photos could be used for. These expectations are almost inevitably violated by practices of data collection in AI. The way consent is put in practice on the internet is not currently sufficient as a way to think about how to treat each others’ bodies.

So how do we think about the shortcomings here, and how do we address them? Let’s think again about what consent means.

Consent is a practical implementation of something normative, so there’s no single standard for what we should expect from consent.

Is consent informed? Informed consent is an idea from bioethics, reflected in federal regulations on human subjects research.

This suggests that consent is conditioned on expectations. If I consent to sex with someone because I believe they are single, then find out later that they are married, did my consent apply?

We often hear the phrase "sustained and enthusiastic." People should be able to withdraw consent at any time. But on the internet it’s not like you can delete every copy of a file from every computer if you change your mind about sharing it.

What about implicit vs explicit? Should we need to sign a contract on the blockchain every time we have sex? I don’t think so. Part of the point of respecting people’s wills is that wills can change. But implicit norms are also failing us if posting a photo on Facebook with the expectation of sharing it with friends implicitly means I am also feeding that photo to an AI.

Underlying all of these ideas is the notion that consent is a way people reason about justly entering into power relations; this is necessarily built on trust that autonomy will be mutually respected.

Autonomy is key. People should have the right to know how their data and bodies will be treated. But not only that, people should have a meaningful ability not to unknowingly participate in practices like predictive policing or porn production. If consent as currently practiced can’t provide that, then it has failed to meaningfully engage with the underlying principle of autonomy.

Synthetic porn won’t solve our problems with consent in deepfakes because the conditions of its production preclude the possibility of individuals freely making informed choices about their data. The cost of not contributing to AI is pretty much to stay off the internet entirely. In the presence of this undue influence, consent is often used by those in power to avoid responsibility for harmful consequences.

Deepfakes as currently practiced largely envisions bodies as objects to be manipulated for the gratification of heterosexual cis men, and gives men like Reddit user “deepfakes” technical tools to make that happen. The men who created deepfakes regard the data which constitutes people’s digital bodies as property. People’s data comes from their bodies, and bodies are inextricable from personhood. People are not property.

Redditor “deepfakes” saw the celebrities in his first videos as not people but interchangeable faces. After Reddit banned r/deepfakes, communities hosting thousands of non-consensual celebrity deepfakes moved to custom knockoff tube sites easily found on the first page of Google search. On these sites, men share and request custom deepfake porn of specific people.

Now, porn studio NaughtyAmerica offers a professional deepfake customization service—creating bespoke franken-pornstars. To AI and the men who wield them, bodies—like anything—are mere pixels to be reconfigured. Distanced by AI from the bodies that produce them, images become a resource to be exploited consequence-free.

AI researchers—and this includes me—need to establish norms and accountability structures which treat images of people as fundamentally different from images of objects, because bodies—as known, understood, and experienced through images—deserve to be treated with dignity. That starts with changing the fact that the people who bear the costs of harmful AI are systematically excluded from its development. This is a problem that pervades across the entire field of AI, from industry hiring and retention, to graduate school admissions, to the cultures of online hobbyist communities.

AI researchers are driving the web toward a future where participating online means being conscripted toward practices that potentially harm others both on and offline. In a possible future, research ethics might meaningfully empower individuals’ non-participation in AI without their knowledge by reframing their questions in terms of autonomy and dignity. Moving from asking “is this data public” to “is it ours to use”; from “who will stop us from using this data” to “who has a stake in its use”. We need AI researchers to think about ethics in terms of autonomy, not just consent.