Attention is a limited resource, and tech platforms capture ours with endless content in order to broker it to advertisers. So much has been said and written.

Recent kerfuffles about harmful content have required tech platforms to rethink their policies around which content is valued and which is not. Earlier this month, YouTube made changes to their monetization scheme that raised the minimum audience requirements for creators to qualify for ad revenue from their videos. In other words, creators have to rake in even more views and subscriptions to get paid.

These efforts to redraw the lines around content have a veneer of public-mindedness to them. Ostensibly, their purpose is to “protect the creator ecosystem”. There are probably ways in which this is true. However, this change comes hot on the heels of controversy surrounding Logan Paul, who remains on the platform and continues to generate ad revenue despite producing harmful content—making it harder for the public to take the company’s claims at their face.

An approach to content moderation in which popularity is conflated with legitimacy is an editorial philosophy by which platforms like Facebook and YouTube profit immensely while abdicating their responsibility as publishers. The most valuable content—the content platforms assume you want to see—is the content that will gather the most views, comments, retweets. More often than we’d like, this can be content that makes people the most shocked, angry, or afraid. The state of things isn’t necessarily because someone in Silicon Valley wanted it this way, but usually due to unintended side-effects of a system structured around the values and objectives of maximally capturing user attention.

All of which is why I’m intrigued by projects which subvert those structures in thoughtful and surprising ways, often by proposing their own alternative structures. For instance, a piece of software called Non Views replaces the count of people who have viewed a video with a count of people currently living who have not viewed the video.

Non Views is defined indirectly, by negation. It inverts what it means to maximize the counter. But it also ties the counter’s value to something variable: the number of people currently living in the world. This number is a construct—in the sense of a constructed object. What makes it meaningful is our ability to describe it in words. And the thing it refers to floats over time; one can’t read the number without at least a momentary recognition of birth and death across the world. This global view puts content in perspective—no matter how popular a video seems, the non-view count is always astronomical. The wider world and time are both indifferent.

Then there’s Astronaut, a website that cycles through uploaded YouTube videos with almost zero previous views. If you press spacebar, the soft chords of Debussy’s Clair de Lune will replace the audio track and shift the mood towards dreamlike contemplation. All of the videos tend to be kind of weird, poorly made, or oddly intimate; not the kind of stuff that would go viral. But these clips give me the sense that posting stuff on the internet that isn't meant to be seen is a radical act, one that rejects the content farm ideology of mechanized production and consumption. These moments with the videos pass by quickly as you quietly bear witness to each piece of digital detritus on its way to the ash heap of internet history.

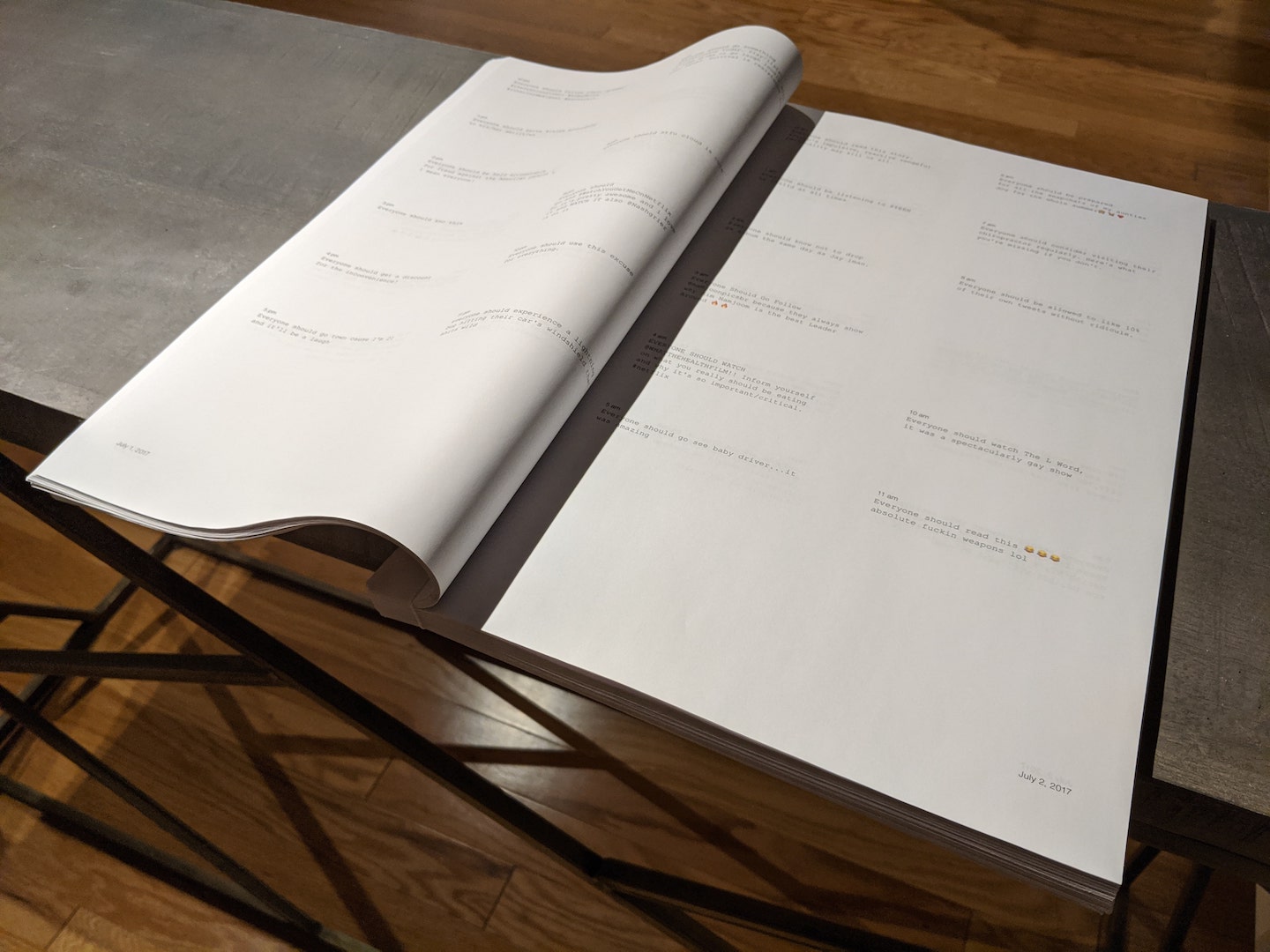

I see a connection between this piece and ideas in my own work—for instance, the book and Twitter bot that I call Everyone Should. Every hour, the bot finds the most recent tweet beginning with the words “everyone should” and retweets it. These messages are collected in the bot’s timeline, and in a large book designed in the form of a diary. Like Astronaut, this project presents an alternative way to select and filter content out of the endless stream. Instead of the complex popularity weighting and demographic targeting algorithms that platforms like Twitter and YouTube use to surface material, the project uses one simple rule. But the resultant accumulation based on a common pattern of language becomes a strange archive of personal and collective moments that are otherwise lost in the flood.

Each of these projects operates structurally. Each has an operating principle anathema to the principle of maximal user engagement upon which the internet is structured. I’m reminded of a paragraph from Umberto Eco’s essay Form as Social Commitment:

The artist who protests through form acts on two levels. On one, he rejects a formal system but does not obliterate it; rather, he transforms it from within by alienating himself in it and by exploiting its self-destructive tendencies. On the other, he shows his acceptance of the world as it is, in full crisis, by formulating a new grammar that rests not on a system of organization but on an assumption of disorder.

The algorithmic feed ranks and re-ranks content in an endless bid for attention. As a result, it churns through content endlessly. The ease with which the algorithm disposes of its own content is its most self-destructive tendency.

As I was collecting my thoughts about the YouTube monetization changes a few weeks after the fact, the changes already felt so far away. So much had happened since then that any particular incident felt like a mere flash in the pan, its weight and consequence receding into distant memory. On the internet, ancient history is made in a matter of seconds.

What these three projects challenge is not only the formal system, but the temporality of the attention economy. All three reject the transitory and linear life cycle that content passes through from creation to relevance to distant memory. Whether by replacing a monotonically increasing view counter with a number that floats with the population; or by bearing witness to small moments in the endless stream; or by accumulating and recycling the digital trash into a new context—all complicate the short half-life of attention online.

These projects share a wistfulness toward the passage of time. They evoke in my mind that hard-to-translate aesthetic principle known as mono no aware, characterized by sensitivity to transience and ephemerality.

By this I mean that they exemplify a different kind of attention—one that isn’t paid, but is practiced. Within this framework, attention is awareness of place, of time, and our perpetual passage through and between. It is a mindfulness that connects us with our environment. In an endless online stream, it is a moment of pause: it is buffering.

Notes

Non Views

Astronaut

Everyone Should

Attention Brokers

Facebook Only Cares About Facebook

Letter of Recommendation: The Useless Machine

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy

Form as Social Commitment

How to Pay Attention