Unsupervised learning algorithms in machine learning impose structure on unlabeled datasets. In Prof. Andrew Ng's inaugural ml-class from the pre-Coursera days, the first unsupervised learning algorithm introduced was k-means, which I implemented in Octave for programming exercise 7. Now, after the fact but with a fresh perspective and more experience, I will revisit the k-means algorithm in Java to implement text clustering. Concretely!

K-means is an algorithm designed to find coherent groups of data, a.k.a. clusters. In the picture above, the data is represented as points on a plot. The colors represent what the algorithm thinks the coherent groups are during iteration 3, even though a human can tell that it hasn't quite found the real clusters yet. Text clustering, however, is a slightly different task. The dataset is a group of text documents; it's not immediately obvious how to represent those as points in space. That's where tf-idf comes in.

Tf-idf Weighting

Before being able to run k-means on a set of text documents, the documents have to be represented as mutually comparable vectors. To achieve this task, the documents can be represented using the tf-idf score. The tf-idf, or term frequency-inverse document frequency, is a weight that ranks the importance of a term in its contextual document corpus. Term frequency is calculated as normalized frequency, a ratio of the number of occurrences of a word in its document to the total number of words in its document. It's exactly what it sounds like, and conceptually simple, and can be thought of somewhat like a fraction of the document that is a particular term. The division by the document length prevents a bias toward longer documents by "normalizing" the raw frequency into a comparable scale. The inverse document frequency is the log (no matter the base, because it scales the function by a constant factor, leaving comparisons unaffected) of the ratio of the number of documents in the corpus to the number of documents containing the given term. Inverting the document frequency by taking the logarithm assigns a higher weight to rarer terms. Multiplying together these two metrics gives the tf-idf, placing importance on terms frequent in the document and rare in the corpus.

static double tf(String[] doc, String term) {

double n = 0;

for (String s: doc)

if (s.equalsIgnoreCase(term))

n++;

return n / doc.length;

}

static double idf(ArrayList docs, String term) {

double n = 0;

for (String[] x: docs)

for (String s: x)

if (s.equalsIgnoreCase(term)) {

n++;

break;

}

return Math.log(docs.size() / n);

}

Cosine Similarity

Now that we're equipped with a numerical model with which to compare our data, we can represent each document as a vector of terms using a global ordering of each unique term found throughout all of the documents, making sure first to clean the input. After we have our data model, we have to compute distances between documents. Visual k-means representations where the data consists of plotted points usually use what looks like Euclidian distance; however, in our representation, we can instead calculate the cosine similarity between the two "arrows" of each document vector. Cosine similarity of two vectors is computed by dividing the dot product of the two vectors by the product of their magnitudes. By creating the aforementioned global ordering, we ensure the equidimensionality and element-wise comparability of the document vectors in the vector space, which means the dot product is always defined. The cosine of the angle between the vectors ends up being a good indicator of similarity because at the closest the two vectors could be, 0 degrees apart, the cosine function returns its maximum value of 1. It's worth noting that because we are calculating similarities and not distances, the optimization objective in this function is not to minimize the cost function, or error, but rather to maximize the similarity function. (Is there a statistics term for this?) I toyed with the idea of converting similarity to an error metric by subtracting it from 1 (since 1 is the max similarity and so at max similarity you get a minimum error of 0). I'm not entirely sure how mathematically sound that is, so I ended up dropping the idea because maximizing similarity works fine.

static double cosSim(double[] a, double[] b) {

double dotp = 0, maga = 0, magb = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

dotp += a[i] * b[i];

maga += Math.pow(a[i], 2);

magb += Math.pow(b[i], 2);

}

maga = Math.sqrt(maga);

magb = Math.sqrt(magb);

double d = dotp / (maga * magb);

return d == Double.NaN ? 0 : d;

}

k-means

In a general sense, k-means clustering works by assigning data points to a cluster centroid, and then moving those cluster centroids to better fit the clusters themselves. To run an iteration of k-means on our dataset, we first randomly initialize k number of points to serve as cluster centroids. A common method, employed in my implementation, is to pick k data points and affix the centroid in the same place as those points. Then we assign each data point to its nearest cluster centroid. Finally, we update the cluster centroid to be the mean value of the cluster. The assignment and updating step is repeated, minimizing fitting error until the algorithm converges to a local optimum. It's important to realize that the performance of k-means depends on the initialization of the cluster centers; a bad choice of initial seed, e.g. outliers or extremely close data points, can easily cause the algorithm to converge on less than globally optimal clusters. For this reason, it's usually a good idea to iterate k-means multiple times and choose the clustering that minimizes overall error.

while (go) {

clusters = new HashMap < double[], TreeSet < Integer >> (step);

//cluster assignment step

for (int i = 0; i < vecspace.size(); i++) {

double[] cent = null;

double sim = 0;

for (double[] c: clusters.keySet()) {

double csim = cosSim(vecspace.get(i), c);

if (csim > sim) {

sim = csim;

cent = c;

}

}

clusters.get(cent).add(i);

}

//centroid update step

step.clear();

for (double[] cent: clusters.keySet()) {

double[] updatec = new double[cent.length];

for (int d: clusters.get(cent)) {

double[] doc = vecspace.get(d);

for (int i = 0; i < updatec.length; i++)

updatec[i] += doc[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < updatec.length; i++)

updatec[i] /= clusters.get(cent).size();

step.put(updatec, new TreeSet < Integer > ());

}

//check break conditions

String oldcent = "", newcent = "";

for (double[] x: clusters.keySet())

oldcent += Arrays.toString(x);

for (double[] x: step.keySet())

newcent += Arrays.toString(x);

if (oldcent.equals(newcent)) go = false;

if (++iter >= maxiter) go = false;

}

System.out.println(clusters.toString().replaceAll("\\[[\\w@]+=", ""));

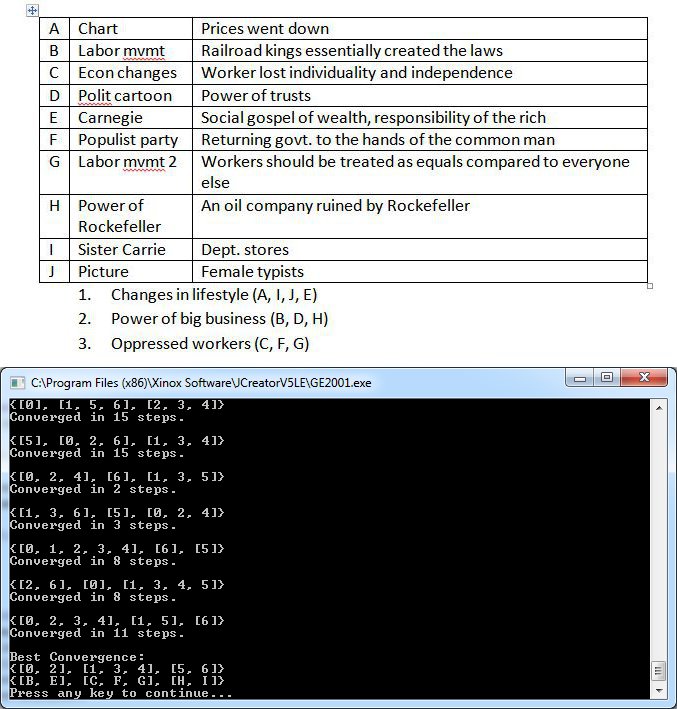

I used as my dataset the Document Based Question from the 2012 AP US History exam free response portion as my corpus and set k equal to 3, a typical number of document groupings used in the essay. When I finished fixing the crazies in my code, I asked a friend to whom I'd never shown my program's results to cluster the documents herself. The results are shown below juxtaposed with the final convergence of my implemented k-means algorithm.

It can be seen that one of the clusters (labeled above as "Oppressed Workers") was exactly the same as produced by a human, while the other two are switched around by one document each after you discount the image documents. The program will consistently give the above best fit clustering from run to run, but it's noteworthy that the local optima to which it converges run to run vary vastly depending on the random initialization. These insights don't really allow us to draw solid empirical conclusions, but it's nevertheless always interesting to compare algorithmic intelligent behavior to human intelligent behavior, no matter how qualitative. It's also reassuring to me as the programmer, because the pitfall with tackling problems like this is that I can't verify absolutely that I am producing correct results. For example, I had a bug in my centroid update calculations before, but I was nonetheless getting coherent lists of group data points as a result. The real telling sign in that instance was the almost invariant number of iterations taken to converge to local optima. I also at one point attempted to implement k-medioids by restricting cluster centers to members of the dataset, but I was uncertain about the comparative accuracy of the results and decided to stick to centroids. My (admittedly messy) implementation can be downloaded here.